|

|

|

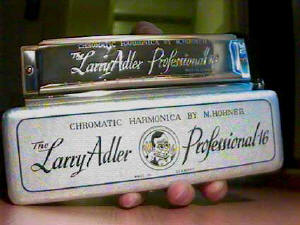

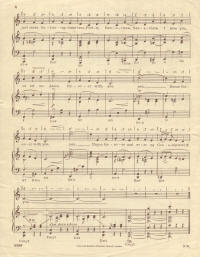

Click the button above to hear Larry

Adler's "Theme From Genevieve" in a version with full orchestra

Click the button above to hear Larry

Adler's "Theme From Genevieve" in a piano and harmonica version

Click the button above to hear

Percy Faith's "Genevieve" - the "love theme ballad," with vocal!

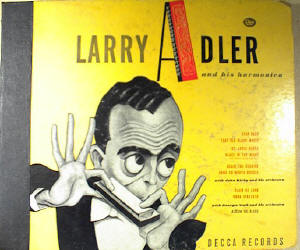

Larry Adler on Scoring "Genevieve"

|

|

Excerpted from

"Me and My Big Mouth" by Larry Adler

Whoever

in their right mind would have thought that a film about a classic car with a

girl's name could become a classic movie in its own right? Certainly not the

Rank Organisation, who rode to fortune on her running board. Or even the stars

themselves, who had no idea they were at the wheel of the surprise hit of the

year.

I'm talking about Genevieve, of

course. Dare I say it -- yes, indeed I dare! -- it was vintage stuff. A breezy,

happy-go-lucky story centered around a veteran car rally from London to Brighton

with all the predictable pitfalls -- if not pit stops -- that beset the quartet

on board. And what a cheery bunch they were: Kenneth Moore, John Gregson, Dinah

Sheridan and the gorgeous Kay Kendall, the bubbly brunette who became known as

the "strumpet voluntary" after her high-spirited rendering on a bugle

during one of the film's high spots. |

| |

|

|

| Me, I wrote and played the catchy

theme... and won an Oscar nomination for it, though my name never got on the

programme on awards night. Ah, Genevieve! That magnificent

lady came thundering into my life on an otherwise unremarkable evening in 1953.

I was idling away at the piano at a party in someone's house in Mayfair, making

up the melody as I went along.

A lady named Vivienne Knight, who

worked in public relations for J. Arthur Rank and would later become Mrs.

Patrick Campbell, came over. "That's nice," she said. "What is

it?"

|

| |

|

|

|

People were always saying that to me.

"Oh, I'm just improvising," I told her. Usual question, usual reply. Next day the phone rang. On the line

was Henry Cornelius, a producer who told me he was in the process of putting

together a comedy about the annual London to Brighton car run. He had heard from

Vivienne that I might be the man to write to score.

"Well --" I was doubtful.

Scoring a film was a highly technical skill. Cornelius insisted that we meet and

suggested Les Ambassadeurs.

|

|

| |

|

|

| OK, there's no such thing as a free

lunch -- even for me. But Les A. was a tempting carrot. Who was I to resistant

offer like that? Over the steak poivre if he put the proposition to me:

could I handle it? |

| |

|

|

| I said no, I couldn't. "Vivienne says you can do it, and

that's all I need to know," growled Henry, in a tone that brooked no

argument. "At least take a look at the script."

When

I read the screenplay, I felt a sudden surge of excitement. You get those

feeling sometimes, don't ask me why or how. But it happens. And when I saw the

rough cut at a private screening room in Pinewood studios -- I was hooked. Line

and sinker!

|

|

| |

|

| The script was charming and witty. The

characters likewise. The atmosphere was bubbling with lighthearted, essentially

British fun where everything that could go wrote did go wrong,

particularly when it came near the bedroom. It became one of the biggest British

screen hits of all time. More than that, anyone who saw it would

forever afterwards associate the name Genevieve with that film. And how

often can you say that of the movie or a name?

Am I right, or am I right?

Oddly enough, one line in the script

decided me. Early in the film, Dinah Sheridan is in the kitchen of her mews

house. She calls up to her husband (John Gregson).

"Alan... proper lunch or proper

dinner?"

That line decided me. It was so quaint.

I had to do Genevieve.

|

| |

|

|

It was a small-time movie, not expected

to make any waves. The lead players were virtual unknowns, so you couldn't call

them stars. Later would be another story. The entire film cost 100,000 pounds,

which is probably marginally less than you pay the guy who massages Stallone or

Schwarzenegger into life in today's overkill movie budgets. My agent called me, and sounded gloomy.

He had asked for 750 pounds. Cornelius pointed out that he didn't have 750

pounds. My price dropped to 500 pounds. Sorry, no. Henry couldn't raise that,

either. Suddenly he didn't seem to have any money at all. Figuratively speaking,

I was blowing in the wind.

|

| |

|

| "Forget it, Larry. This is a small

time outfit. Let it go, and we'll find another picture for you later in the

year."

He

was right, of course. But one thing was nagging me. "Nobody has ever ask me

to compose before." I thought of something else. "Besides, I love the

film and I want to do it."

They offered me a percentage: 2 1/2

percent of the producer's share. It doesn't sound like much, and it wasn't. But

as the film took off I became richer than the actors, who each got a flat fee of

1500 pounds -- yes, that's all -- with no participation in the proceeds.

It's an old story, but it's still sad

when it happens. John, Kenny, Kay and Dinah -- if only they had been given a

slice of the cake. When that movie opened to rave reviews ("one of the best

things to have happened to British films over the past five years" -- Gavin

Lambert; "Who he -- Ed?") it was making a profit within the first

month. As for me, I happily put my children through college on the proceeds.

But behind the scenes, trouble loomed.

Not for the cast or crew, but for me. America was nervous. Meaning Hollywood and

New York, where the power play was centered. What was the problem? In two words

-- Larry Adler.

|

| |

|

| The word got out that I was writing the

score for Genevieve. Henry Cornelius was one of the good guys, an amiable soul

celebrating his 40th birthday as he ushered Genevieve safely through the winning

tape on Brighton sea front on that June afternoon. As a would-be actor he had

studied under Max Reinhardt, but he had really marked his card in the public

perception as someone rather special with his 1949 comedy Passport to Pimlico,

two years before Genevieve took to the road. |

|

| |

|

| Henry called me into his office. He

looked nervous and upset as he gestured to me to a chair. It seemed that a call

had come through from a top executive at the Rank Organisation. The message was

terse and to the point: get Larry Adler off the picture. |

| |

|

|

"They've been told that if your

name is on the film, it won't get an American release," he said, with a

hopeless shrug. The shadow of the blacklist had reached

across the Atlantic. I looked at him. "Corny," I said. "You are

the one who put me on the film. If you want to take me off, just say so. I'll

go. I don't want to do anything to hurt you, or the film. Do you want me off

it?"

He shook his head. "No. I love the

stuff you've turned in. I don't want to lose it."

"OK," I said. "Let my

agent battle it out with Rank. I'll keep working on the score."

|

|

| |

|

| Cornelius agreed. Later he would

describe my methods as "chaotic" -- but they worked. I would get a

sudden inspiration, and write notes down on scraps of paper which I stuffed into

my pockets, or pasted into a manuscript book. When I got to the studio I emptied

my pockets onto a table, and went through the score with the musical director,

Muir Mathieson. Mathieson was the Scots-born veteran of

literally hundreds of British film scores, either as composer or conductor, all

the way back to the 1930s. His credits read like a musical role of honour, from The

Scarlet Pimpernel (1935) with Leslie Howard, Laurence Olivier's masterpiece Henry

V (1944) and Brief Encounter (1945) with Trevor Howard and Cecilia

Johnson to The Seventh Veil (1945) with James Mason and, later, Lord

Jim (1965) which starred Peter O'Toole in the Joseph Conrad epic of far

eastern skullduggery.

|

| |

|

| Here was Mr. Mathieson, floundering

through the notes of what Henry Cornelius dubbed my "route map," and

looking as lost as if he'd plundered into Hampton Court maze. Corny told one interviewer: "Even

Larry didn't know how the pieces of paper followed each other. He works by

memory, with some crazy method of his own. There was only one thing to do -- we

put our heads down for eight terrible hours trying to get the music into some

sort of order, and finally got the route map together.

|

|

| |

|

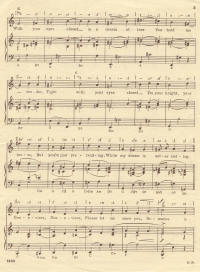

| "It worked like this: you play the

first four bars on page 5, then the last 23 bars on page 1. Repeat the four bars

on page 5, then play the little 'bridge' which is on a separate piece of paper.

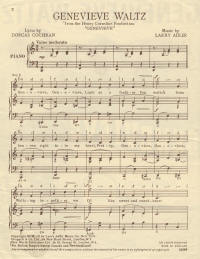

You finish this sequence with 10 bars, ringed in red ink, on page 13!" The final score, in the words of critic

Herbert Kretzmer (who would later write the script of Les Miserables),

turned out to be "one of the freshest and most enchanting soundtracks ever

heard on a British film."

I guess that exonerated me.

What it didn't do was spare me from the

wrath of the zealots in Hollywood who were still under the McCarthy yoke, and

thirsting for blood.

Behind the scenes, the in-fighting

began. I had no written contract, just a verbal agreement. That was always good

enough for me, as long as I knew the parties involved. In this case, it left me

with no cards to play. I had to make a compromise if I wanted to stay on the

film -- leave the billing to the Rank Organisation.

My agent was firm. Do it, Larry. You've

really got no choice. So, OK, I did it. But not without qualms. I had never had

this kind of pressure before, and I didn't like it one little bit.

United Artists distributed Genevieve in

the U.S.* She was booked for a New York opening run at the Sutton Cinema on East

57th Street to see if she would take off across the country.

Six weeks before the opening date, the

Rank Organisation received the word that the U.S. distributors wanted my name

taken off the print. Oh-oh!

They got it. Genevieve opened in

New York to excellent reviews, with the name Larry Adler conspicuous by its

absence from the credits. Suddenly I was Public Leper No. 1. I have to say that

few things have hurt me more than having my name taken off the billing -- though

I got some satisfaction when most of the critics gave me credit for the music.

Out of the blue, that February, came a

note from Ira Gershwin. "Didn't you tell me that you had composed the score

for Genevieve? The music has been nominated for an Oscar -- but composer

is named as Muir Mathieson."

And so it was. The ballad had been

recorded by Percy Faith for Columbia, my own soundtrack was out on the same

label, the music was published in Britain by "Larry Adler Music." No

good. I was o-u-t -- and I was one angry man. But what could I do?

Once the nominations were in to the

Motion Picture Academy, they couldn't be changed. Rank had touched the forelock

to the czars of Hollywood. I was the fall guy. On Oscar night my name was never

even mentioned in despatches. But in the end it was that wonderful Russian

composer Dimitri Tiomkin, of High Noon fame, who collected the treasured

gold plated gnome for The High and the Mighty.

Muir Mathieson was a gentle Scotsman, a

peer among his own kind. I couldn't figure out how he had the effrontery to

accept the Academy nomination for composing the score when both he and I knew it

was my work, my blood, sweat and tears that had created it. Christ, we had been

standing together on the sound stage at Shepperton and as he conducted the

orchestra!

Some weeks later, I met him as a

charity function and faced him with it, point-blank. "How could you?"

I demanded, man to man.

"But Larry," protested the

grand old Scot. "I just thought the Academy was giving me a special award

for services to British film music."

I believed him.

The odd thing about that film is that

no one saw it coming. In Germany, it laid a large egg. Rank hated it -- yes,

hated it. Initially they put it on the shelf, and for a time it looked as if Genevieve

wasn't going to take to the open road of a nationwide release at all.

As for me, I had gone through all sorts

of agonies after seeing the completed film and a private cinema in Soho, the

first movie I had ever scored. Why, people were actually talking over my

beautiful music, drowning it with dialogue and sound effects! The lesson I

learned was that the only time the film composer ever hears his score the way he

wrote it is when it is being recorded on the sound stage.

While we were still in limbo, another

picture opened for six-week run at the Odeon, Leicester Square, the flagship

cinema for the Rank Organisation. It was a flop and it had to be taken off. The

only film around was Genevieve.

The rest -- well you know it.

* Actually, Genevieve was distributed

in the U.S. by Universal.

|

Offsite Larry Adler Links

[ Up ] [ Genevieve Rally July 2002 ] [ Models and More ] [ Bookshelf ] [ Genevieve Links ] [ Is This the Real Mr. McKim? ] [ What's Wrong Here? ] [ The 'Very Easy' Genevieve 50 Years On Quiz ] [ Genevieve Picture Gallery ] [ Music by Larry Adler ] [ Genevieve's History ] [ The Cast ] [ Filming Locations ] [ Making "Genevieve" ] [ London to Brighton 2000 ] [ Audio Clips ] [ Site Map ] [ Thanks ] [ Down Under ] |

|

|