By Elizabeth Nagle, excerpted from Veterans of the

Road,

Ms. Nagle's 1955 history of the Veteran Car Club.

|

| |

|

|

When

Henry Cornelius announced his intention of making a film

depicting a fictitious Brighton Run, and asked the club to help, it was

never imagined that a unique page in the club's history was

about to be written, a page that would forever be part of the

permanent pattern, and yet one which told a story apart from the

rest. It is a story of fun and frolic tempered with caution, of patience

and forbearance mixed with trepidation, of laughter, excitement,

tumult and hard work. |

|

|

In the beginning, there were two factions: Mr.

Cornelius knew what he wanted: he had his script and

his stars; he needed advice and cars. The committee,

on the other hand, knew what it did not want: the

wrong sort of film showing a mockery of the run. But it

had the cars. It had, too, its own ideas of the demands that film

directors were inclined to make, while Mr. Cornelius had more

than a faint notion of how to get his own way. "Read the script,"

he said. "We want your help, your cars and your blessing." In

the end, he got all three and before very long, goodwill was added

for full measure. |

|

The first reading of the script brought cries of alarm: "You

can't do that, or that or THAT! and who has ever heard of an

ancient Lanchester with a bonnet ?" "That's precisely where you

come in," was the patient reply. "Authenticity is what we want,

and only you can give it." There was much anxiety on that race

back, for was it not the very antithesis of the club's objects? A

series of meetings began and gradually these heart-burnings were

eliminated. Steadily, too, a mutual trust disposed of the problems

and brought about a partnership which worked smoothly and well.

On the club side, a great deal of the credit for this belongs to

Evelyn Mawer. He became the club's representative, Mr. Cornelius'

technical adviser-in-chief and the Secretary's prop and stay, to say

nothing of his own and his car's appearances on the set. |

|

| |

|

|

In theory, it seemed a

simple matter for the club to produce two

cars for three months, thirty-five on one day in Hyde Park, ten

here, fifteen there and twenty in Brighton. In practice, it assumed

the proportions of a military operation. Members had to be invited

to take part; they had to know dates, but these depended on the

weather; they had to know places, but many of these were uncertain;

they had to know duration of shooting, but that was controlled

by the sun. Above all, the choice of "Genevieve" herself and her

chief rival was the major problem. The shooting of the film was to

continue from September to November, so that these two cars

would be away from their owners for the vital months of preparation

for the Brighton Run. The risk of damage, too, was great; it had

been suffered before in film work, and many

members, although prepared to drive their cars

themselves for shooting, were not willing to hand them

over to a doubtful fate. |

| |

|

| Henry Cornelius had set his heart on a

Lanchester for Claverhouse's car, but all his charm and persuasion were of no

avail. The gears of the early Lanchesters are too

intricate for inexperienced

fingers ; their owners spoke with one voice, and the united answer

was "No." Both the club and the Director were keen to feature a

British-made car; a Wolseley and then a Humber was proposed for

"Genevieve" but there were none available for the task. Finally,

Norman Reeves and Frank Reece came to the rescue: the former's

1904 Darracq was cast to play "Genevieve" and the latter's Spyker,

the only Dutch car in the club, made a superb adversary. Better

still, a member of Mr. Reeves' staff, Charlie Cadby, himself a

member of the club, became the star cars' keeper for the duration

of the filming, and it was thanks to him that they were still running

at the end of it. |

| |

|

|

|

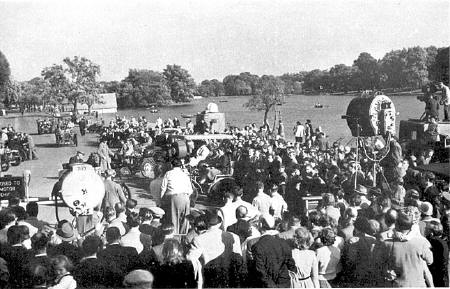

The chief contestants settled, the

H.Q. telephone progressed from very warm to red hot.

Thirty-five Veterans in Hyde Park on a weekday was no

small undertaking, and not just any Veterans would do;

they had to be beautiful, burnished and brightly

coloured; some of them had to be available for continuation shots

and their drivers had to be prepared for anything. That was the

easiest qualification; it is part of a member's make-up. Owners

pointed out with polite firmness that they did work, that short

notice was impossible (a fact that the Secretary knew only too well),

and that getting wet on a real "Brighton" was

one thing BUT. ... Finally, all was

resolved, members turned up trumps as they always

did, and thirty-five impeccable Veterans joined the directors,

technicians, pantechnicons, cameras, arc lamps and stars beside

the Serpentine in Hyde Park. The adventure had begun. |

| |

|

| All those who have seen the film know what

followed, but what they did not see was the turmoil

and seeming confusion; the starting and stopping, the

endless waiting; the driving to and fro, the standing

and looking, the watching and wondering. The queue for

coffee and the lunch under the trees; the orders, counter-orders

and the constant repetition; the grumbles and humour, the sudden

laughter. Dinah Sheridan doing her knitting, Kay Kendall struggling

with Suzy, John Gregson struggling harder with "Genevieve" and

Kenneth More handling the Spyker with surprising skill. Master

of it all was Henry Cornelius, patient,

imperturbable and persuasive. |

| |

|

|

From Hyde Park the scene shifted to the Mall,

Constitution Hill, Westminster Bridge, all the old

familiar landmarks of the Brighton Run. The cars got

mixed up with the Life Guards, a Buckingham Palace

sentry and incredulous onlookers who stood and stared.

There was one glorious day in Brighton with brilliant sun and blue

skies and Madeira Drive looking as it never will in November .

There were the twos and threes who carried out their orders in

divers places, the faithful who turned out anywhere at any time

and lastly, the grand finale in the studios. |

What's wrong with this picture?

|

| Not once was shooting delayed by the absence of

a car; not once did a breakdown spoil a sequence. By

the time it was all over,

thirty-nine members and their cars had achieved between them a

total of ninety-five appearances, and apart from the Darracq and

the Spyker, the driving throughout had been done by the owners,

who accustomed themselves to a quaint situation with a speed

which was astonishing. If any doubts had existed of the goodwill of

the club or the reliability of its cars, they were dispelled with

alacrity, and if members had doubted the capacity of film directors

for hard work, understanding and humour, their fears foundered

on the first day. |

| |

|

| The outside shots requiring the cars were

completed by the end of October, but Mr. Cornelius was

quick to realise that the thirty-five in Hyde Park

with a few hundred onlookers hardly did justice to a

real "Brighton" entry surrounded by thousands of spectators. Consequently, the

start of the "live" run on November 2nd, 1952, was

filmed, and despite the bad weather, the pictures that were obtained

add much to the authenticity of the film, and immortalise a scene

which has become a traditional part of London's November

pattern. Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius had attended the club's cocktail

party the evening before, and were in action early the next morning,

anxious to absorb that atmosphere of its own which only the real

thing could give them. |

|

| |

|

| For the next six months, the club had little to

do but wait and wonder. By Christmas, the Darracq and

the Spyker were home again and the task of restoring

them to their former fitness begun. In the spring,

plans were laid for the club's share in the premiere and the

Rank Organisation's co-operation with the Coronation Rally which

coincided with the opening showing of the film in London. As the

weeks went by, speculation on the picture grew. Rumours from the

studios were few and guarded, and the Director refused to be drawn.

"Just wait and see," he said-an expression which had been found

to be his favourite months before. |

| |

|

| At last, May 27th became a

reality, and all the members who had taken part, and were able to

accept the Rank Organisation's invitation to attend, turned up in

force to see what had been done with their contributions, over which

they had, after all, exercised only remote control. Harry Browell,

who, as chairman of the committee, had done much to found the

happy partnership between the club and Mr. Cornelius, was

appointed the V.C.C. critic, and in his own inimitable fashion this is

what he wrote: |

| |

|

On May 27th at the Leicester Square Theatre the first showing took

place of the film with which many members

were so energetically concerned. All the suitable

circumstances of a premiere had been laid on and

bouquets offered and accepted and nice things said and

reciprocated.

Before many feet of film had passed it

became clear that the V.C.C. were not the only

ones to exert themselves and that Henry Cornelius

and his cheerful team had made a film that may be shortly described

as very, very good indeed. ..

Highlights to the eye of your critic were a

magnificent three-cornered row with the driver of

a Skimpworthy Special, an abominable hotel in

Brighton and a tantalising hold-up during a

desperate return journey caused by a little girl

(Mr. Cornelius' own) laboriously taking back into

stock an ice cream she had dropped in the road.

The handling of the cars is all most

reasonably done and the whole thing complete in

every detail except the density of the Brighton traffic

and no Nagle or Milvain.

(Which only goes to show that even a

V.C.C. critic can miss a "comic turn.")

|

|

|

For the general release a few months later,

members throughout the country turned out their cars,

and it shortly became apparent that the club was

concerned with a film which appealed to the public as

few had done in recent years. Before long, the film had gone

overseas, and was immediately hailed as a tremendous success.

In the United States it inspired several special "Genevieve" rallies,

and the Horseless Carriage Club of Colorado staged a run for

Veteran cars from Denver to Brighton (Colorado) to coincide with

the film's showing there. They obtained the

regulations of the Brighton Run from the club, and

made every effort to conform to them as closely as

their own circumstances would permit-the essential

differences being a day of brilliant sunshine with a temperature of seventy-six

degrees, and the age limit of the cars, which had to

be 1914 to attract sufficient competitors. The British

Consul for the Rocky Mountain Region, and his wife,

were guests of honour and travelled in a model "T"

Ford. Official greetings were exchanged between the

Mayor of Brighton, Colorado, the Lord Mayor of

Westminster and the Mayor of Brighton, England, and

good wishes between the Presidents of the two clubs.

Every competitor received a special "Genevieve" dashboard plaque and

among the trophies presented was one named after the British club. |

| |

|

| From Australia came news of similar runs in

Adelaide and Sydney, and in Melbourne the film ran

continuously for months. One old lady there attended

every morning performance and after thirteen weeks

became the guest of the management. Nearer home, the

story was the same: in France, Germany and allover the Continent

it has drawn huge crowds, and in Holland it was linked with the

club's rally to Alkmaar, where "Genevieve"

herself, the Darracq which must surely be the most

famed car in the world today, was given a tremendous

welcome of her own. |

| |

|

| There is no doubt that this remarkable film has

carved its own niche in contemporary life, and a

fictitious Brighton Run, with its fantasy and frolic,

has appealed to people all the world over, as has the

genuine article with its unique history. Maybe, the fiction and

the fact bear only a remote resemblance to each other; maybe,

the world's audiences wonder where the one

begins and the other ends. The clue can, perhaps, be

found in Genevieve's own introduction to her public : |

| |

|

For their patient co-operation the makers of

this film express their thanks to the Officers and

Members of The Veteran Car Club of Great Britain.

Any resemblance between the deportment of the

characters and any Club members is emphatically

denied-by the Club.

|

| For his patience, perception and goodwill, Henry

Cornelius is now an honorary member of that club.

Thus, a venture which began as an unknown quantity has

developed into a film of world-wide appeal. In a large measure,

the growth of the club has followed a similar pattern. Slow at first,

it has steadily gathered momentum until its twenty-fifth birthday

witnesses an enthusiasm unimaginable during its first. Started by

three friends, it has grown from a small band to a national and then

international body, and members have come from

all walks of life, from all and sundry trades and

professions to share a common interest and build a

common pride. Now, more than 1,300 of them can

celebrate a Silver Jubilee which has been accomplished by them

all, and rejoicing in the ownership of close on 1,000 cars, can look

forward to a growing entity which, by its very nature, is beyond

time and prediction. |

[Genevieve Home

Page] ["Making Genevieve" Page]

|